Nearly half of doctors are rethinking their careers, finds COVID-19 survey

Key Takeaways

The coronavirus has devastated America, with 9.7 million infected and 236,000 dead as of this writing. But the pandemic has also had a devastating effect on medical providers, particularly those on the front lines of care. As measured by just one benchmark, as many as one in 16 Americans (5.9%) infected with COVID-19 is a healthcare worker, according to new information from the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

MDLinx took the pulse of US physicians to find out how the pandemic has affected them both personally and professionally. Our survey was sent out twice to different physicians, in July and September 2020, with a total of 1,251 responses. More than one-third of these were primary care physicians, with a range of specialists—including oncologists, gastroenterologists, neurologists, psychologists, and many others—comprising the remainder.

COVID-19’s ripples through medicine

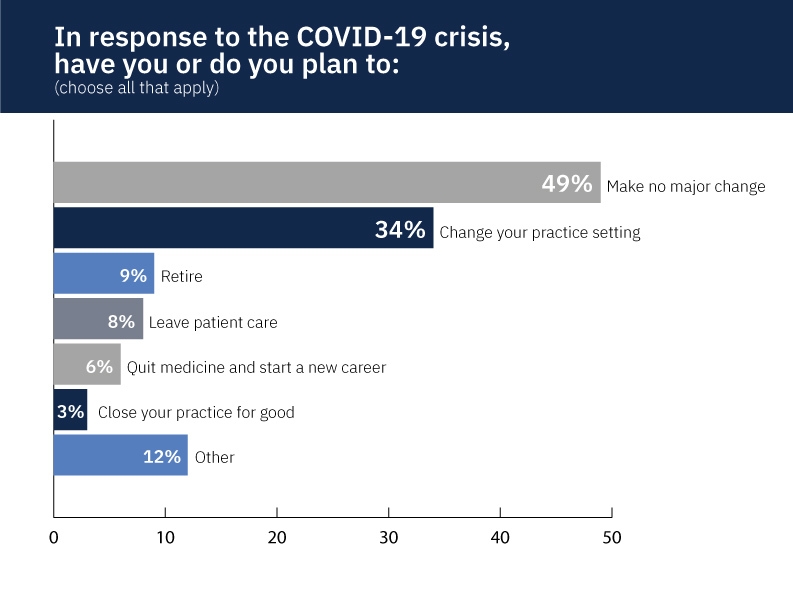

A shock to the system—as COVID-19 has been to the healthcare system—is enough to make anyone second-guess what they’re doing with their life. In our survey, more than 48% of respondents reported that the COVID-19 crisis has caused them to seriously rethink their career or their practice.

The numbers are even higher among primary care physicians. About 50% of internal medicine doctors and as many as 55% of family physicians reported they’re seriously rethinking their careers or practice.

What are these doctors thinking—or rethinking? About one-third (34%) said they plan to change their practice setting or that they’ve already done so. For many, this has meant switching to telehealth visits either part or all of the time. For others, this has meant cutting back hours.

“COVID-19 has accelerated adoption of telemedicine and likely [will have a] ripple effect on technological innovation in medicine in the years to come,” said an oncologist from California.

About one in 10 doctors (9%) say they plan to retire. One family physician said the COVID-19 crisis has inspired her to “figure out a way to retire earlier.”

Eight percent of respondents are thinking about leaving patient care or have already done so. “I switched to pure clinical research immediately before the crisis and am glad I did,” said a neurologist from Georgia. A neurologist from Illinois noted that he’s “reconsidering going into consulting.”

About one in 20 doctors (6%) said they’re planning to quit medicine and start a new career. Said an Alabama internist: “I have definitely second-guessed my decision to practice medicine. Patients have in general been more irritable during this stressful time.”

A gastroenterologist from Texas said, “I wish I could quit medicine and make a career in something else—but too late.”

Only 3% of respondents said they’re planning to close their practices for good.

Let’s look at some of those numbers and consider their implications: If 3% of doctors close their practices, 6% leave medicine for a new career, and 9% retire, that’s a sudden loss of 18%—almost one-fifth of the physician workforce. Such a loss would overwhelm a healthcare industry that’s already shorthanded.

“The United States needs its health-care workers to see it through this crisis,” wrote emergency medicine physician and disaster control expert Thomas Kirsch, MD, MPH, in an essay in The Atlantic. “But there are no replacements on the shelf. They can’t be built, trained, or repurposed from other jobs. Unless the country does dramatically more to provide them with the equipment they need to do their job safely, to assure them they will be cared for if they fall ill, and to provide their family with a measure of security, it risks losing them. What happens when they need to be quarantined? When they start to die? Or don’t come to work?”

The answer is unknown. “It’s hard to plan after that happens,” Dr. Kirsch wrote.

But perhaps there’s a silver lining to this crisis: The COVID-19 pandemic has re-inspired some physicians. They’ve suddenly found more meaning in their careers.

“It has actually galvanized me,” said an Iowa hospitalist. “I think I am privileged to provide inpatient medicine at just a moment in history when the need is so great. The potential to help the greatest number of people is great!”

Similarly, an internal medicine physician in Michigan took the initiative to “set up community service COVID testing. [We] tested over 3,000 patients with PCR swabs and 2,000 antibody tests.”

Side gigs to make ends meet

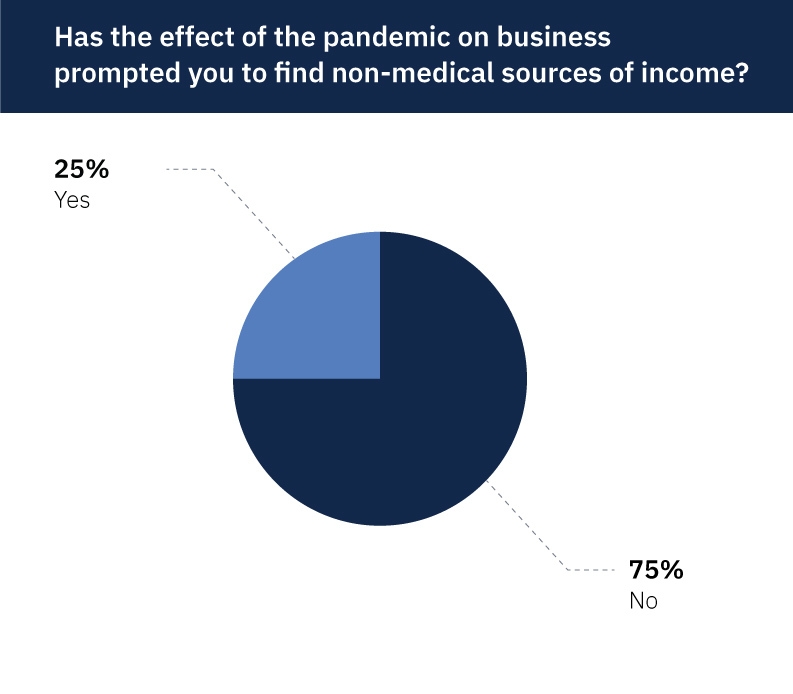

As fewer patients with non-coronavirus issues came into hospitals and medical offices, revenue streams threatened to dry up. To that end, one-fourth of respondents (25%) sought and found non-medical means of income.

These innovative and entrepreneurial physicians are doing everything from consulting to driving an Uber, from real estate investment to house cleaning. While trading stocks or doing chart review has been a means for many, “selling stuff on Amazon” or eBay brings in a bit of income for others. Still others are tutoring, teaching, farming, selling cosmetics, and making medical masks.

A Band-Aid solution

In an MDLinx survey conducted in March 2020, 82% of respondents expressed that the government should provide financial help to physician practices. In April, the Trump administration rolled out the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which established several new temporary programs to help businesses during the COVID-19 outbreak. These included the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), Economic Injury Disaster Loans and Emergency Grants (EIDL), and Express Bridge Loans (EBL).

We asked physicians if they enrolled in these programs, and whether they were approved. About one-fourth (23%) of respondents reported they applied for relief programs under the CARES Act. Of these, the overwhelming majority (90%) applied for PPP, but 23% also applied for EIDL, and 13% for EBL.

The good news: 83% of respondents who applied for PPP were approved, as were 16% for EIDL, and 11% for EBL. The bad news: Some of these programs—notably the PPP—quickly ran out of money and shut down.

Although the CARES Act programs may have been a Band-Aid solution for a few months, the pandemic continues on, with no further relief in sight.

“It's clear that doctors should be given more economic relief including student loan forgiveness,” noted a gastroenterologist from Illinois.

“I volunteered to work in the ICU during COVID even though it was outside my scope of practice,” said an oncologist in New Jersey. “Our hospital system at the time said they would ‘make us right’ financially since we obviously took a hit in the office setting. To date they have refused to pay us for our time or efforts.”

Hopeless, helpless, and honorable

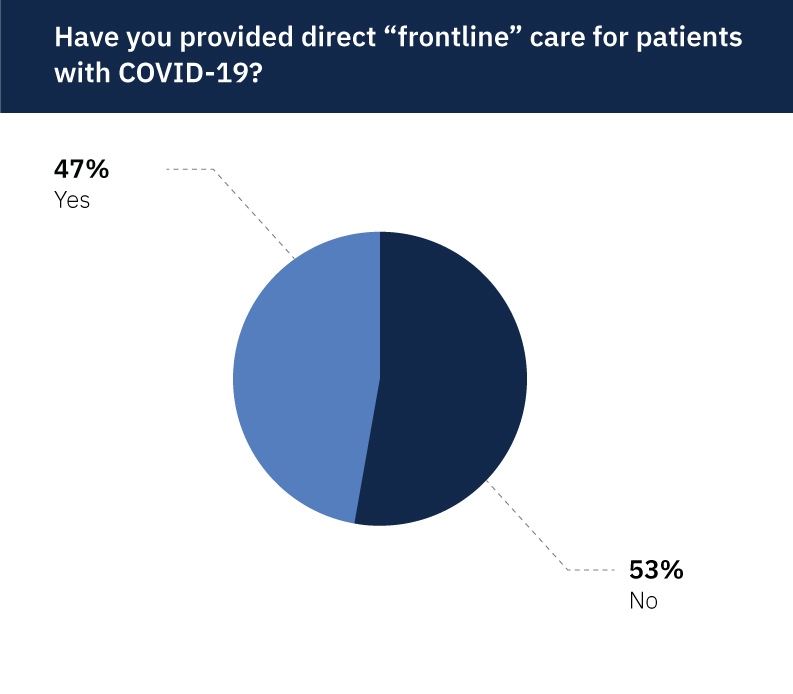

Speaking of caring for patients with COVID-19, nearly half (47%) of respondents said they’ve provided direct, frontline care for patients with the virus.

Their reactions to providing frontline care were as wide-ranging as the spectrum of physicians themselves. Many called it “stressful” and “scary.” Others called it “challenging,” “difficult,” “exhausting,” and “frustrating.” Yet others called it “fulfilling,” “important,” and “rewarding” (though not in the financial sense).

“Horrible. Devastating,” said one New York physician. “In the beginning (March, April) the number of patients was endless and so many died.”

Many doctors described having a mix of different emotions all at once. “It is daunting and humbling at the same time. Makes you realize how brittle and vulnerable we all are,” said an internal medicine physician in Virginia.

“Never more proud to be a doctor than now,” said a hospitalist in Louisiana. “Providing care for COVID patients and providing comfort to them and their families has been emotionally draining but rewarding as well.”

One statement came through loud and clear: The need for personal protective equipment (PPE) far outweighed the supply.

“PPE is scarce. We receive two surgical masks per week and use face shields for every encounter, which become hot and fogged up,” said a family physician at a Florida medical clinic. “It is physically uncomfortable to work drenched in sweat.”

“There is never enough PPE,” agreed a critical care specialist in Missouri. He also voiced other frustrations: “[T]oo many delays in testing, families don't understand what’s going on, data changes every week (this has improved somewhat), and nothing we can offer actually works to fix COVID.”

“I am a hospitalist who worked on the frontlines while the bloated overpaid hospital administrators ran from the hospital (and Zoomed from their manicured backyards) using a spineless excuse of ‘saving PPE’ as a reason they couldn't help,” said a physician from Massachusetts. “It showed me that hospital administration is superfluous and only are there to siphon off our legitimate payments into their bloated bank accounts.”

Other respondents who are, or have been, on the front lines were equally exasperated, worried, and aggravated by what they experienced.

“I feel hopeless at the lack of good treatment options,” said an internal medicine resident in Texas. “I was also overwhelmed by the death when working in a COVID ICU.”

Said a locum tenens doctor in Illinois: “I saw very fragmented policies from hospital to hospital regarding: 1. information on patients who were COVID negative versus still pending test results; 2. Monitoring employees for COVID; 3. PPE supply.”

“The problem is not me getting infected, it is bringing it home to my family and elder parents. So the cost is very, very personal,” said one Texas physician. Then he added: “Don’t make heroes out of us and call this a war [because] then it gets easy to sacrifice us.”

“Scary.” That’s how a Pennsylvania neurologist described her experience. “Declared a man brain dead and the saline from corneal reflex assessment splashed me in the face. Luckily I was in one of our few PAPRs [powered air-purifying respirators].”

Hospitalists and critical care physicians aren’t the only ones dealing with the onslaught of patients. “I’m working 12-hour days including Saturday to accommodate the huge increase in anxiety and depression,” said a New Jersey psychiatrist. “I am working virtual only and there is no end to the need in my community.”

Coronavirus comes for doctors, too

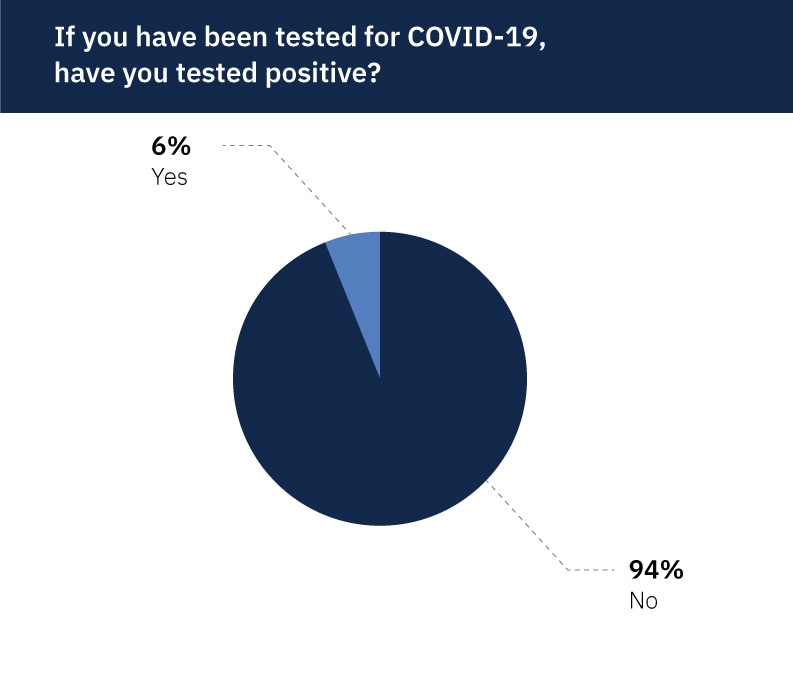

According to our survey, more than 44% of physicians have been tested for COVID-19. Of these, nearly 6% of respondents reported testing positive for the disease—the same rate as that reported by the CDC.

“I contracted COVID at my hospital and was very sick for 2 weeks. Thankfully I recovered,” said a hospitalist from California. “It made me decide to uproot to a different state to practice medicine.”

We received one response letting us know that the physician we sent the survey to had died from COVID-19.

Final note

Perhaps this hospitalist from Iowa summed it up best:

“I think many people study and train their whole lives, waiting for a moment to really put that expertise to its perfect use. Those of us who practice hospital medicine are now being presented with just that opportunity. We get to help a lot of people, and really make a difference. This isn't a time when you find yourself doing one mindless chest pain rule out after another… But now, with the COVID pandemic, we can shake the dust off, step up, and really save a lot of lives like we all thought we would when we first applied for medical school.”